James Island County Park, Charleston, SC

January 25 - 30, 2020

Charleston was originally a walled city. The area to the right is now where The Market is, and the area to the left and beyond is now landfill and where the Battery and Rainbow Row are located. The road at the top is now King Street.

On Sunday, January 26 we went to see the H. L. Hunley.

On the night of February 17, 1864, the submarine H. L. Hunley attacked and sank the USS Housatonic off the coast of Charleston, SC. Historical records show that the Hunley crew signaled to shore that she had completed the mission and was on the way home, but instead they mysteriously vanished. That night, history was made. The Hunley became the first submarine ever to sink an enemy ship in combat. But why had she disappeared? Lost at sea for over a century, the Hunley was located in 1995 and raised from the ocean floor in 2000. Divers had tried to locate her for over a century, but she was found outside the area they were searching, towards the ocean. All the crew were found at their stations, looking like they had just gone to sleep. To this day researchers don't know exactly what happened, but there are several theories. For more information go to their website at www.hunley.org. It's quite interesting.

Afterwards we went to Magnolia Cemetery, where they buried the crew members. There were actually three sinkings, the first where all the crew died, the second where some of the crew died, and the third and most famous where all the crew died. There are memorials for all three crews at the cemetery.

On Tuesday, January 28 we went back into Charleston to continue our working on our Museum Mile Tickets.

First we saw the Aiken-Rhett house.

Built in 1820 by merchant John Robinson, the Aiken-Rhett House is significant as one of the best-preserved townhouse complexes in the nation. Vastly expanded by Governor and Mrs. William Aiken, Jr. in the 1830s and again in the 1850s, the house and its outbuildings include a kitchen, the original slave quarters, carriage block and back lot. The house and its surviving furnishings offer a compelling portrait of urban life in antebellum Charleston, as well as a Southern politician, slaveholder and industrialist. The house spent 142 years in the Aiken family's hands before being sold to the Charleston Museum and opened as a museum house in 1975. This house is being preserved, meaning that the Charleston Museum has preserved the house and buildings as they were when they took them over. Between an earthquake, damp weather, and hurricanes, time has not been kind to the house. Some parts of the house don't look too bad, and others and in great disrepair. However you could still get a sense of what life was like in the house.

The slaves lived on the second story of the kitchen, laundry, and stables. There was no cross ventilation and must have been hot in the summer and cold in the winter.

Then we went to see the Nathaniel Russell house. It was quite different than the Aiken-Rhett house in that it has been beautifully restored.

Then we went to see the Nathaniel Russell house. It was quite different than the Aiken-Rhett house in that it has been beautifully restored.

Nathaniel Russell arrived in Charleston from Bristol, Rhode Island in 1765 and established himself as a merchant and slave trader. His 1789 marriage to Sarah Hopton Russell produced two daughters, Alicia and Sarah, and in 1808 the Russell family moved to their new townhome at 51 Meeting Street. Accompanying them were as many as eighteen enslaved people who toiled in the work yard, gardens, stable and kitchen. Russell spared little expense in the construction of his home, regarded as one of Charleston’s finest in its era with geometrically shaped rooms, elaborate plasterwork ornamentation and formal gardens. The defining architectural feature of the home is a three-story, cantilevered, flying staircase whose “…sweep is broad, treads are deep, and the rise perfectly proportioned and easy of ascent,” according to Nathaniel Russell’s great-granddaughter Alicia Hopton Middleton. A National Historic Landmark, the house has been restored as nearly as possible to its 1808 appearance.

The garden was pretty too.

Our final stop of the day was the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon.

Completed in 1771, the Old Exchange Building is the site of some of the most important events in South Carolina history. Over the last two and a half centuries, the building has been a commercial exchange, custom house, post office, public market, public meeting place, city hall, military headquarters, jail, and museum.

The lower floor was the 'dungeon'.

The main floor had two large rooms on the north and south sides of the building, used for public meetings and social events.

The upstairs is the Grand Hall.

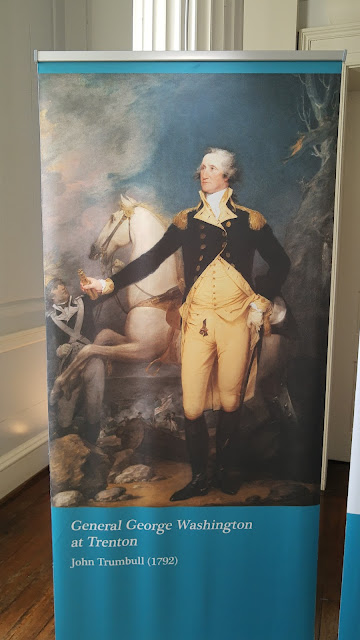

In 1791, when President George Washington spent a week in Charleston as part of his Southern tour, the Old Exchange was the site of various activities in honor of his visit, including a fancy dress ball. To commemorate his visit the city leaders commissioned a portrait of Washington. You can read how that went below.

On Wednesday, January 29 we went to the Edmondston-Alston house.

Pictures were not allowed so I only have the outside of the house. It's a shame because the inside is beautifully restored. You can see pictures on their website, www.edmondstonalston.org.

The house was built in the late Federal style by Scottish shipping merchant Charles Edmondston at the height of his commercial success. In 1825, it was one of the first substantial houses to be built along the city's sea wall away from the noisy wharves and warehouses further up the Peninsula. But a decade later, economic reversals during the Panic of 1837 forced Edmondston to sell his house. It was purchased by Charles Alston, a member of a well-established Low Country rice-planting dynasty who quickly set about updating the architecture of his house in the Greek Revival style. The house has remained in the Alston family since 1838. Among the elements Alston added were the third story piazza with Corinthian columns, a cast-iron balcony across the front, and a rooftop railing bearing the Alston coat of arms. During the Civil War they had a front row seat to the start of the war and all the bombing. The Union bombed Charleston for over 500 days straight, but amazingly the house was never hit. The house next door was hit and destroyed.

Our last stop was the Heyward-Washington house.

Built in 1772, this Georgian-style double house was the town home of Thomas Heyward, Jr., one of four South Carolina signers of the Declaration of Independence. A patriot leader and artillery officer with the South Carolina militia during the Revolutionary War, Heyward was captured when the British took Charleston in 1780. He was exiled to St. Augustine, Florida, but was exchanged in 1781.

The City rented this house for George Washington's use during the President's week-long Charleston stay, in May 1791, and since then it has traditionally been called the "Heyward-Washington House." Heyward sold the house in 1794 to John F. Grimke, also a Revolutionary War officer. It was acquired by the museum in 1929, opened the following year as Charleston's first historic house museum, and was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1978. It also was restored and holds original furnishings.

This is thought to be the room that George Washington slept in, but not in that bed.

That night we went out to dinner at Hyman's Seafood with some friends.

Tomorrow we head back home. Roving on...

The heavens declare the

glory of God, and the firmament shows His handiwork. Psalm 19:1